The sistrum was one of the most sacred musical instruments in ancient Egypt and was believed to hold powerful magical properties. It was used in the worship of the goddess Hathor, mythological character of joy, festivity, fertility, eroticism and dance. It was also shaken to avert the flooding of the Nile and to frighten away Seth, the god of the desert, storms, disorder, and violence. Isis, in her role as mother and creator, was often depicted holding a pail symbolizing the inundation of the Nile in one hand, and the sistrum in the other hand. It was designed to produce the sound of the breeze hitting and blowing through papyrus reeds, but the symbolic value of the sistrum far exceeded its importance as a musical instrument.

Ancient Greek historian, Plutarch, speaks of the powerful role of the sistrum in his essay, “On Isis & Osiris”:

“The sistrum makes it clear that all things in existence need to be shaken, or rattled about, and never to cease from motion but, as it were, to be waked up and agitated when they grow drowsy and torpid. They say that they avert and repel Typhon by means of the sistrums, indicating thereby that when destruction constricts and checks Nature, generation releases and arouses it by means of motion.” (Plutarch, Moralia, Book 5, “On Isis & Osiris,” section 63)

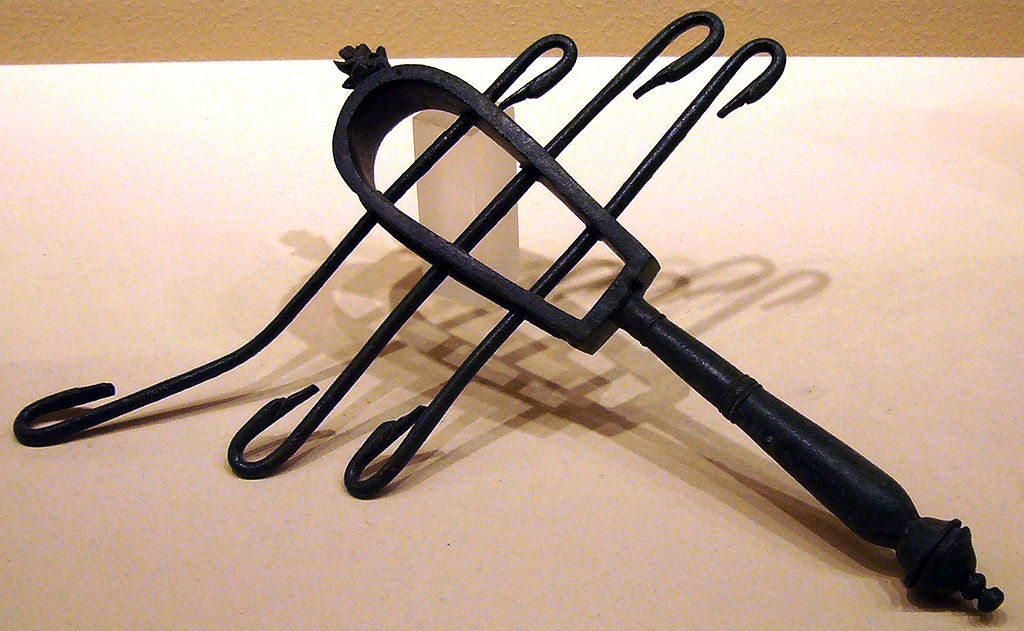

The sistrum consists of a handle and frame made from brass, bronze, wood, or clay. When shaken the small rings or loops of thin metal on its movable crossbars produced a sound that ranged from a soft rattle to a loud jangling. Its basic shape resembled the ankh, the Egyptian symbol of life, and carried that hieroglyph's meaning. Archaeological records have revealed two distinct types of sistrum.

A sistrum (plural: sistra or Latin sistra;[1] from the Greek σεῖστρον seistron of the same meaning; literally "that which is being shaken", from σείειν seiein, "to shake"[2][3][4]) is a musical instrument of the percussion family, chiefly associated with ancient Egypt. It consists of a handle and a U-shaped metal frame, made of brass or bronze and between 30 and 76 cm in width. When shaken, the small rings or loops of thin metal on its movable crossbars produce a sound that can be from a soft clank to a loud jangling. Its name in the ancient Egyptian language was sekhem (sḫm) and sesheshet (sššt).

Sekhem is the simpler, hoop-like sistrum, while sesheshet (an onomatopoeic word) is the naos-shaped one. The modern day West African disc rattle instrument is also called a sistrum

Egyptian sistrum

The sistrum was a sacred instrument in ancient Egypt. Perhaps originating in the worship of Bat, it was used in dances and religious ceremonies, particularly in the worship of the goddess Hathor, with the U-shape of the sistrum's handle and frame seen as resembling the face and horns of the cow goddess.It also was shaken to avert the flooding of the Nile and to frighten away Set.

Isis in her role as mother and creator was depicted holding a pail, symbolizing the flooding of the Nile, in one hand and a sistrum in the other.[8] The goddess Bast often is depicted holding a sistrum also, with it symbolizing her role as a goddess of dance, joy, and festivity.[

Sistra are still used in the Alexandrian Rite and Ethiopic Rite. Besides the depiction in Egyptian art with dancing and expressions of joy, the sistrum was also mentioned in Egyptian literature.The hieroglyph for the sistrum is shown.

The sistrum continued to be used in Egypt well after the rule of the pharaohs. Rome's conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, following the death of Cleopatra and Mark Antony, helped spread the cult of the goddess throughout the Mediterranean and the rest of the Roman world. The Hathor heads were interpreted as Isis and Nephthys, who represented life and death respectively.

Worship of the goddess Isis became extremely popular in the Greco-Roman period and during this time, the sistrum became inextricably tied to Isis. Temples to Isis were built in every major city, perhaps the largest and most richly decorated being in Rome, near the Pantheon. The temple and its surrounding porticoes were decorated with beautiful wall paintings, some of which show priests or attendants of Isis holding a sistrum.

In Greek culture, not all sistrums were intended to be played. Rather, they took on a purely symbolic function in which they were used in sacrifices, festivals, and funerary contexts. Clay versions of sistrums may also have been used as children’s toys.

Minoan sistrum

The ancient Minoans also usthe sistrum, and a number of examples made of local clay have been found on the island of Crete. Five of these are displayed at the Archaeological Museum of Agios Nikolaos. A sistrum is also depicted on the Harvester Vase, an artifact found at the site of Hagia Triada.

Researchers are not sure yet if the clay sistra were actual instruments that were used to provide music, or instead were models with only symbolic significance. But, experiments with a ceramic replica show that a satisfactory clacking sound is produced by such a design in clay, so a use in rituals is probably to be preferred.[12]

The sistrum today

The senasel (sistrum) remained a liturgical instrument in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church throughout the centuries and is played today during the dance performed by the debtera (cantors) on important church festivals. It is also occasionally found in Neopagan worship and ritual.

The sistrum was occasionally revived in 19th century Western orchestral music, appearing most prominently in Act 1 of the opera Les Troyens (1856–1858) by the French composer Hector Berlioz. Nowadays, however, it is replaced by its close modern equivalent, the tambourine. The effect produced by the sistrum in music – when shaken in short, sharp, rhythmic pulses – is to arouse movement and activity. The rhythmical shaking of the sistrum, like the tambourine, is associated with religious or ecstatic events, whether shaken as a sacred rattle in the worship of Hathor of ancient Egypt, or in the strident jangling of the tambourine in modern-day Evangelicalism, in Romani song and dance, on stage at a rock concert, or to heighten a large-scale orchestral tutti.

Classical composer Hans Werner Henze (1926–2012) calls for the flautist to play two sistra in his 1988 work Sonate für sechs Spieler (Sonata for six players).

West Africa

Various modern West African and Gabon rattle instruments are also called sistra (plural of sistrum): the calabash sistrum, the West Africa sistrum or disc rattle (n'goso m'bara) also called Wasamba or Wassahouba rattle. It typically consists of a V-shaped branch with some or many concave calabash discs attached, which can be decorated.

(Left) Attracting Negative Charge to Anode Core via Resonance : (right) Tuning Forks

(Left) Attracting Negative Charge to Anode Core via Resonance : (right) Tuning Forks

[Resonance / Attraction] Tuning Fork

Traditionally seen as the ships mast, explains how charge is transferred to stars. For further information see Anubis.